You’re standing in a pitch-black room with five other people. It’s dark. No light. You can’t even see the hand in front of your face. Everyone is trying to find the exit. In the panic-stricken darkness, you hear scattered voices: “I think the door is over there,” “I just found a wall over here,” “The exit is probably a door.” You could spend hours collecting everyone’s theories about where the door might be and observations of the room. Or you could use a light to illuminate the room for a hot second. Suddenly, everyone is grounding on a single observation. There’s one way out, a low-key steel door in the corner. But there’s the chair blocking the path. The route is obvious, and everyone can start moving in the same direction.

In this situation, many designers stand in that dark room waiting for someone else to find the light switch. Meanwhile, the designer has a flashlight in their hand and hasn’t thought to turn it on.

The Bottleneck of Waiting

What’s wrong with this picture? Designers sitting idle, waiting for stakeholders to answer questions about a project? “What should the user flow look like?” “How should this behave?” “What’s the priority?” “What are the important features to include?” Meanwhile, project timelines tick by, and designers haven’t made any progress. Everyone gets frustrated.

Waiting designers create a bottleneck that kills momentum. When designers sit around asking clarifying questions, stakeholders are getting impatient. They start making decisions without design input. They bring screenshots from competitors and say, “Just make it like this.” They think you’re being difficult when you ask for more time to “design”.

But here’s what’s really happening: you’re asking people to navigate in the dark when you’re the one with the flashlight.

The Paradox of Solving Problems

There’s another very important reason why waiting for answers doesn’t work well (beyond the bottleneck). Research in psychology consistently shows that people are terrible at telling you what they want. In dating studies, what people say they want in a partner doesn’t match who they actually choose when speed dating. Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert’s research demonstrates that we’re remarkably bad at predicting what will make us happy. Consumer behavior studies reveal that over 60% of people who say they’ll buy something don’t actually purchase it when the time comes.

Steve Jobs understood this when he said a lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them. He recognized a basic truth about human psychology: We want to see to believe.

The problem runs deeper than preferences. Design researcher Nigel Cross discovered that design problems can’t be fully understood until they’re solved (and sometimes not even then). We’re dealing with what’s called “wicked problems,” where the problems have so many facets that it’s nearly impossible to completely understand. The act of solving it often reveals the true nature of what we’re solving for. It’s a paradox: the act of solving the problem reveals how to solve the problem.

This means understanding the problem is only possible by exploring solutions. You can’t explore solutions by asking questions or making up answers to fill the gap that questions pose.

The Flashlight Method: Creating Solutions

This is where designers need to step up and shine a light on the path forward. Instead of asking what stakeholders or users want, start showing them all what’s possible. This is the key: showing them.

The fastest way to do this? Sketch your way to clarity. In 30 minutes, you can externalize multiple concepts and put concrete meaning behind abstract, word-based ideas. When someone says “make it more intuitive,” you can sketch three different approaches to improve the clarity of navigation and let them react to actual options instead of debating the definition of intuitive.

Here are some of my favorite rapid modeling techniques:

- Crazy 8s: Grab a piece of standard paper and fold it 3 times so you end up with 8 rectangles. Force yourself to sit down and sketch out 8 different ideas. Don’t overthink it, just draw. Good ideas, bad ideas, all the ideas. This forces you past your first obvious choice into more interesting territory.

- Wireflow sketching: Draw the actual steps someone would take with very crude thumbnails that serve as an outline of the screen a user might see at each step. This is helpful for visualizing the future journey.

- Concept mis-modeling: Sketch the core idea in the wrong context or format. If you’re designing a dashboard, draw it as a car dashboard, a control room, a video game HUD, or what it might look like on a roll of toilet paper. Or, try drawing it with a completely different medium like sidewalk chalk. See what you learn from contextual shifts.

- Feature hierarchy visualizations: Instead of debating what’s most important, sketch the interface with different features emphasized. Show version A with data display prominent, version B with primary actions prominent, version C with learning content front and center.

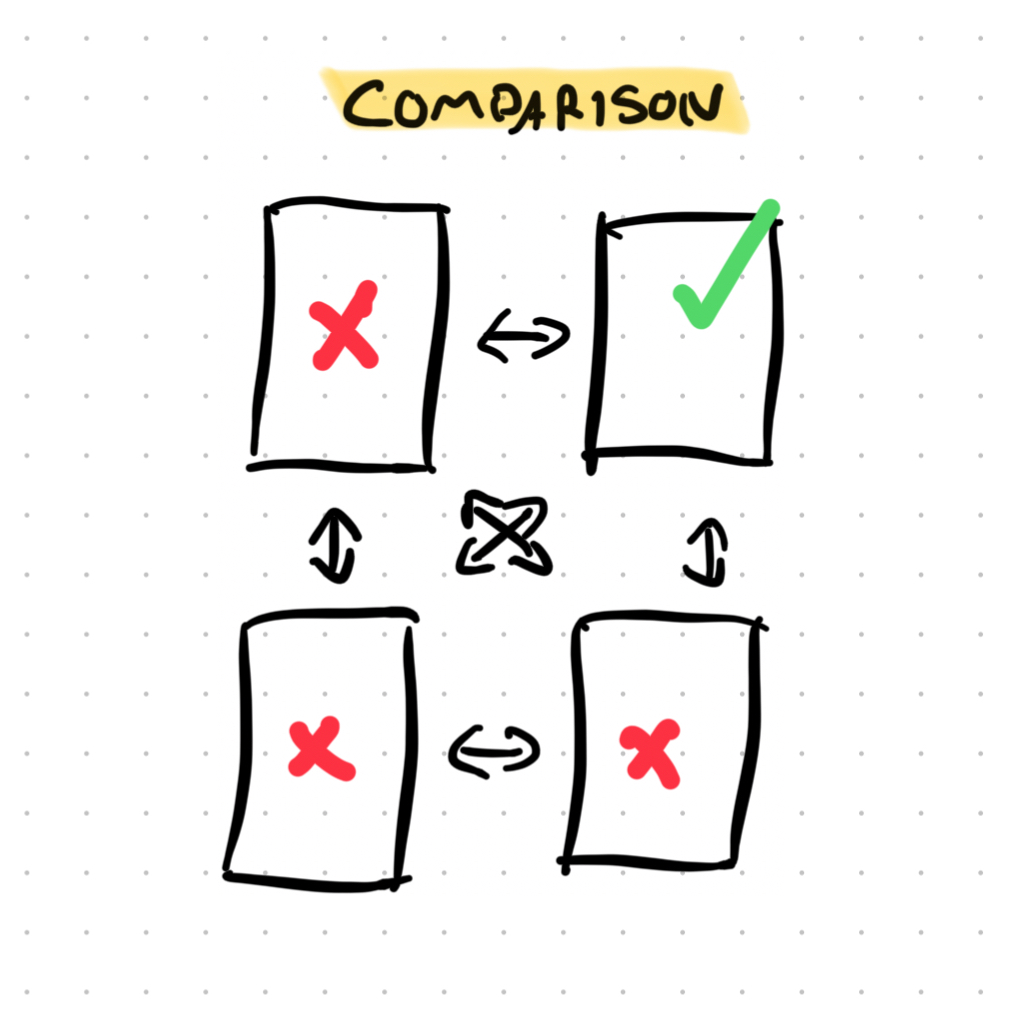

Why do all of this? Because options inform each other. Options get responses. And the magic happens in those responses. When you show concrete possibilities, you get concrete feedback. Instead of vague wishes, you hear:

“Not that, here’s why…” (Now you understand their constraints.)

“That’s a good start, but it’s missing…” (You’re getting specific direction.)

“Yes, that works because it solves…” (You’ve found alignment.)

Each response teaches you something specific about the problem you’re solving. You’re not just getting feedback; you’re conducting research on the solution fit. And the bonus is that you’re loading up fall-back ideas and context into your brain and your stakeholders’ brains. You’re learning together.

But Isn't This Wasting Design Time?

I can hear the objection: "Isn't sketching multiple concepts a waste of time? Shouldn't we get requirements first, then design the right solution?"

Here's what's actually wasteful: spending weeks building a solution you think works, only to discover it doesn't fit the problem. Sure, it passes user testing, but it lacks the value resonance you were striving for.

Sketches are cheap. Thirty minutes of exploration costs almost nothing compared to weeks or months of development in the wrong direction. It’s so common to become so focused on efficiency that we've forgotten exploration is what makes design valuable (I’ve explored this in an article called the sanitization of design).

What about AI? Couldn’t AI just prompt its way to solutions faster? Maybe. But the problem will inform solution fit, and AI struggles to target problems with the nearly infinite variables that make up design challenges. AI can't understand your specific context, stakeholder concerns, or watch people's faces react to ideas in real-time. Don't mistake tool efficiency for design effectiveness. That said, AI may be a useful tool to compare your ideas with what it comes up with, so don’t ignore it either.

Designer as Pathfinder

This approach transforms how you work and how others see your work. When you come to the table with multiple solutions instead of asking for answers, you become the person who moves projects forward. You’re not waiting for someone else to make decisions. You’re creating the conditions for good decisions to happen.

This shift benefits your growth as a designer in ways that sitting around asking questions never could. First, it forces you to think critically about problems instead of passively collecting requirements. You have to make choices about what to prioritize, how to organize information, what interactions to emphasize. These choices build your design maturity.

Second, you get to critique faster. Instead of spending weeks gathering requirements, you could have your first design critique in hours. You learn through failure (iteration), which is the best teacher design has to offer. Every sketch that doesn’t work teaches you something about the problem you’re solving.

Third, you build a catalog of experience. Each time you model a solution and see how stakeholders respond, you’re adding to your mental library of what works and what doesn’t. This experience becomes invaluable when facing similar problems in the future.

Most importantly, this positions you as someone who solves problems, not someone who takes orders. When stakeholders see you as the person who can illuminate unclear situations, they start bringing you into conversations earlier. They trust your judgment more. They see design as essential to figuring out the path forward, not just making things look pretty at the end. Design becomes the enabler, not the blocker.

Show Them the Way Out

Let’s go back to that dark room. Everyone’s standing there confused, bumping into walls, debating where the exit might be. The room is dark for everyone, including you. Stakeholders aren’t inventing answers or direction because they’re trying to be difficult. They’re stumbling around in the dark just like everyone else.

But you’re the one with the flashlight.

When you model solutions, you’re not just showing your ideas…you’re illuminating the problem space so everyone can see what’s actually there. You’re revealing constraints nobody knew existed. You’re making the abstract concrete so people can respond with specificity instead of guessing.

The most valuable designers aren’t the ones who wait for perfect briefs or complete requirements before they start. They’re the ones who can take ambiguous problems and quickly show what solving them could look like. They create clarity where none existed before.

Don’t wait for someone else to turn on the lights. Pick up the flashlight and help everyone discover the way out. This is the job of design. Have fun!