We have a language problem in design. Not a vocabulary problem...a mental model problem. Listen to how we talk about our work:

- "I need to defend this decision."

- "We have to push back."

- "I'm fighting for the best option here."

- "I got them to concede."

- "We need to educate the stakeholders."

These aren't just phrases. They expose how we've come to think about design's relationship to the other people in the broader product development process. We don't view design as collaborative improvisation, but as an opposing force. Not as ensemble work, but as solo combat.

I've been using language like this for years. Proudly, as a badge of honor showing my "design stripes". They roll right off my tongue without a second thought. Except one day in a meeting, I heard myself say: "We need to push back..." and it struck me. What the heck was I saying? I searched for different words but had to think about how I could phrase it differently. Surprisingly, it took way too much effort.

Looking at those words later, I realized: I was describing collaboration as combat. Advocacy as opposition. Partnership as conflict. But, I'm not the only one. This is a learned behavior that I've been mimicking for years. I've seen it in training materials, books, famous design talks, and more.

Where did this mental model come from? Why has it become so normalized? And what's it actually costing us?

The Opposition Model in Action

Here's what this model looks like in practice. Walk into any design team meeting and you'll hear variations of these phrases. We say them with conviction. We think they demonstrate commitment to good design. We believe they show we won't compromise on quality.

The language is everywhere once you start listening for it. In standups. In critiques. In stakeholder meetings. In Slack threads. Heck, it's woven throughout our industry content.

Now imagine sitting in a jazz ensemble. The bassist is laying down the foundation. The drummer is setting the tempo. The piano is establishing the harmony. Each musician is listening, responding, playing off each other. That's how ensemble work functions: multiple voices creating something together.

But, let's say one musician decides to ignore everyone else. Plays louder, dominating the soundscape. They play in a different key. They refuse to listen. What happens?

Well, the music falls apart. The ensemble can't function. The harder that musician pushes their own solo, the more discord they create. Eventually, the other musicians stop inviting them to play. Not because they're not talented, but because they make collaboration impossible.

This is what's happening with the opposition model. Every time we "push back," every time we "defend," every time we "fight," we're not strengthening our position. We're creating discord where there could be harmony. We're damaging the relationships that need to support collaborative work.

We think this makes us sound strong. Like effective advocates. Like people who care deeply about craft. Like the only people empathetic to users.

But here's what it actually signals: war. Working with design will be a battle. Every interaction will require engaging the enemy.

What the Language Reveals

This opposition model has some innate assumptions about how design work happens. Here's what our language communicates:

"Defending decisions" reveals an expectation of attack

When we position ourselves as defendants preparing for trial, we're assuming adversarial intent before anyone even speaks. The signal sent: "I don't trust you, and I don't think you trust me."

"Pushing back" invites reciprocal resistance

This language creates exactly what it claims to counter. When we push, we're pushing against our partners, not the problem we're unified around solving. So, people push back. Not because they oppose good design, but (at times) because we've framed the interaction as oppositional. The signal: "Working with design means digging in, not opening up."

"Fighting for the user" makes the business the enemy

This phrase declares war on the people who fund the work and make the product possible. It creates a false choice between users and business, as if serving one demands betraying the other. The signal: "You don't care about people. Only we do." (And sorry, you're not TRON.)

"Winning & Conceding" turns collaboration into zero-sum competition

When we talk about winning arguments or refusing to concede, we've made it impossible for everyone's constraints to matter simultaneously. It's my way or your way with no mutual wins. The signal: "If I don't get exactly what I want, I've failed."

"Educating stakeholders" positions us as superior

There's often a subtle tone with this statement that casts us as superior and others as ignorant students who just need to be schooled. The signal: Condescension dressed up as helpfulness.

Notice the pattern? Every phrase assumes scarcity. Scarcity of trust. Scarcity of good outcomes. Scarcity of understanding. Scarcity of respect. We've built our language around the belief that there isn't enough to go around. Whether it's influence, space for good work, or room for design to matter...we're poised to fight over scraps.

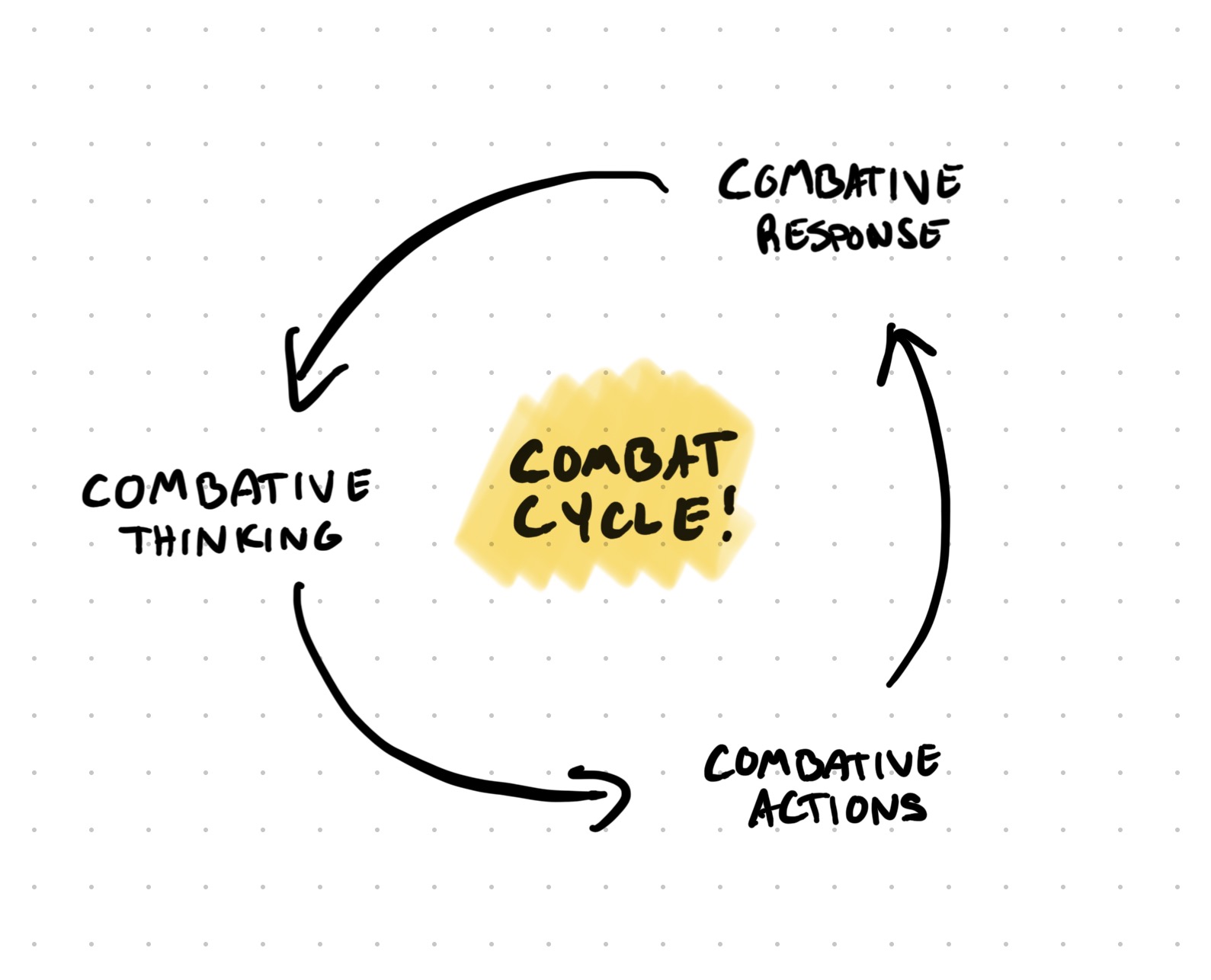

But, the scarcity isn't real. It's self-created. Every combative phrase makes the thing we fear more likely. These words are undermining everything we're trying to accomplish together.

What Hostility Costs Us

Although it appears we may have adopted some of the language from our corporate counterparts, it doesn't matter. This mental model and its language are costing us dearly.

This isn't unique to design. Corporate culture has been saturated with military metaphors—'target customers,' 'attack the competition,' 'defend market position'—for decades. Research shows this language creates adversarial environments and undermines collaboration. But what might sound decisive in a boardroom becomes destructive in collaborative work.

This "design opposition mental model" burns bridges. Every combative phrase trains people that working with design means preparing for a fight. Eventually, they stop bringing us into early conversations. They figure things out first, then ask us to handle the last mile of work. They route around us. We become exactly what we swore we'd never be: the people who "make things pretty" after the "real decisions" are made.

We're reinforcing the very dynamics we complain about.

A few years ago, I was working with a senior leader on a major project. They were smart, driven, cared about doing the right thing for the project. We should have been natural partners.

But I kept "pushing back" on the timelines. Kept "defending" the authenticity of my research. I kept "fighting for the user" as the answer. I thought I was being a strong advocate. I thought I was doing my job.

Instead of "winning the argument", I destroyed the relationship. I blew the trust and partnership I once had with them. Instead of targeting the problem, I targeted someone that should have been my closest partner and ally.

I'd become a liability. Not a collaborator. Instead of focusing on solving the user and business problems, they had to focus on the other problem...me. I was a giant distraction.

That's what the "us vs them" mentality of design costs us. We sacrifice the collaboration we need to do good work. And then we complain about not being able to do good work.

It's ridiculous now that I look back on it.

The Alternative: Design as Ensemble Work

There's a different mental model that's more effective. It shifts design from a solo to an ensemble. Where our role isn't to overpower or "win" but to listen and create something together.

It will change how we talk about our work and partner with others. Our thinking will drive productive actions.

- When we explain our decisions, we're not defendants in a courtroom. We're musicians proposing how music parts fit together. "Here's how this layout supports both user goals and our technical constraints." Instead of us vs them, we're explaining how the arrangement works.

- When we disagree with a direction, we're not drowning out other instruments. We're suggesting a different progression that amplifies the whole piece. "Here's what we're seeing from users that points us in this direction." We use "together" language, providing data for consideration.

- When we advocate for users, we're not declaring war on the business. We're finding the harmony between business and user needs that complement each other. "I want to make sure we're solving for the business needs and the user goal so they support each other. Here's how we could do both." It's not fighting, it's harmonizing.

- When we navigate disagreements, we're not trying to win zero-sum competitions. We're finding the arrangement where everyone's part contributes. "Here are three paths that balance everyone's constraints and goals. Which makes the most sense given our priorities?" It's not me or you, it's choosing the best that works for everyone based on priorities.

- When we share expertise, we're not condescendingly lecturing others on the finer points of music theory. We're listening to what each person brings and building on it together. "When we were developing these ideas, we were considering these two industry standards, and we've applied them in this way. I'd love your input on how these interact with our project goals." We're not in our ivory tower, we're inviting others to build the music with us.

This model assumes good intent. It brings harmony instead of dissonance. It invites collaboration instead of demanding the spotlight. It channels our efforts towards the problem, rather than at each other.

The bassist doesn't fight the drummer over who controls the rhythm. They listen to each other and lock in together. The pianist doesn't defend their chord choices or drown out the lead guitarist. They voice their chords to make space for the melody. Each musician brings their constraints—their instrument's range, the song's structure, the key they're in—and uses those constraints to create something coherent.

This is design as ensemble work. Not a few solo artists trying to perform all at once.

Changing the Model

Think about what happens in a band when one musician consistently refuses to listen. The first time, everyone may adjust, thinking "that's weird". They compensate. The music continues. The second time, people get frustrated, and adapting is burdensome. But over time, trust erodes. Communication breaks down. Things get heated. Eventually, the other musicians start rehearsing without you. Before you know it, you're not getting called for gigs, and you wonder why.

This is what happens when we operate with adversarial behavior. One combative phrase creates a small rift. Another widens it. Over months and years, they accumulate. We stop getting invited to early conversations. We're brought in later, after key decisions are made. People work around us. By the time we notice the exclusion, the relationship damage is severe.

And this isn't just individual. Every designer who operates from this model confirms the "design stereotypes". News of this behavior spreads. That makes it harder for the other designers on the team. We're collectively weakening the foundation that supports the ability to do good work.

If you're reading this and feel like you're in this spot...all is not lost. It's not too late. Ensembles can rebuild trust. Our mindsets shape our behavior. Change your thinking and begin repairing what was damaged. We can't undo years of discord overnight, but we can stop creating new rifts. We can start listening where we've been soloing. The ensemble can find its groove again. A few positive experiences like this will begin to cast doubt on the negative past.

I'll admit, I still slip into opposition language at times. Especially when I'm stressed or exasperated. I'm still working on it. But I'd rather sound uncertain and be effective than sound strong and be a jerk.

Jazz works because musicians listen to each other, not ignore each other. They respond. They build on what others play. They integrate ideas together. Nobody solos through the entire song. Everyone serves the music.

So, start noticing when opposition language shows up in your words. Catch it. Apologize for it. Reframe it. The work matters too much to keep creating discord.

Change is uncomfortable. At first, these new words will feel awkward or less powerful than the combative ones. But that discomfort means we're learning. And the collaboration that follows will be worth every uncertain sentence.